THE SALVADORAN EVANGELICAL CHURCH

From Obscurity to Prominence

The evangelical church of El Salvador has a history that reaches backwards to almost a hundred years. The first missionaries arrived in 1896 were sent out by the Central American Mission (CAM). The political environment was tense during those years due to an anti-Catholic sentiment on part of the ruling liberal party. In 1886 the Salvadoran legislature approved a new constitution for the country that allowed freedom of worship for all citizens giving a terrific blow to the Catholic hegemony of religion at that time. The CAM begin their work in Ilopango and San Salvador. In 1904 missionaries from the Canadian Pentecostal church arrived. This work grew even faster than the CAM churches due to the liveliness and participatory nature of the services. Soon, an indigenous group known at the Apostles and Prophets, began. They developed their roots in the very poor of the nation. Their growth was so spontaneous that public disorder often characterized their services. Because of this disorder, the government decreed that all pastors had to get a license to preach and present to the government a list of the church’s membership. Due to other chaotic conditions within the Pentecostal churches, a new organization emerged in 1930 and for that organization the First Pentecostal Congress held in the city of Ahuachapan. The new organization was named, “General Council of the Assemblies of God of El Salvador,” under the direction of the Reverend Ralph Williams.

Apparently, those first years were difficult due to the homogeneous nature of the Central American people and their Catholic tradition. Church planting was difficult, for the people were suspicious of any new philosophy that foreigners brought. Slowly more missionaries begin to arrive and over the years the number of evangelical churches begin to increase. The Central American Mission, The Assemblies of God, The Church of God of Cleveland, Tennessee, and the American Baptist all sent missionaries as well as other churches from the United States. From San Francisco de Gotera in the east to Ahuachapan in the west, small and humble evangelical churches soon were appearing in every little town. By the year 1932 there were more than two hundred missionaries working in El Salvador with a local church body of approximately 200,000 people.

In 1932, El Salvador experienced a significant uprising known as the Salvadoran peasant uprising or the “La Matanza” (The Massacre). The uprising was primarily fueled by social and economic inequality, deep-seated grievances, and political unrest. The main cause of the uprising was the extreme disparity between the wealthy landowning class and the impoverished peasant, mostly Indian population. These poor faced harsh working conditions, low wages, and limited access to land and resources such as education, and health care. Additionally, there was widespread dissatisfaction with the government’s domestic policies, which further fueled the discontent.

The uprising was led by a charismatic indigenous leader called Feliciano Ama, who was a member of the Pipil people. He united various indigenous communities and peasants to fight for their rights and demand land reform. Ama’s leadership and ability to mobilize people played a significant role in the uprising. As more people joined the uprising, the Salvadoran government, under the dictatorship of General Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, responded to the uprising with brutal force. The government launched a violent crackdown, leading to the massacre of thousands of indigenous people and peasants. The exact number of casualties remains a subject of debate, but estimates range from 10,000 to 40,000 individuals.

It’s important to note that this uprising marked a turning point in Salvadoran history, leading to increased political awareness and activism, which ultimately contributed to social and political changes in the country. The brutal suppression of voiceless poor also created long memories that discouraged participation of evangelicals in national politics.

At the time of this uprising, the evangelical movement was having a difficult time just existing. The one communality that the many peasants had was that they were all poor. Many had been previously disposed of their ejidal lands, and therefore, when leftist and communist movements began organizational drives during those years, many evangelical members were also caught up with the possibility of justice. Marxist and union leaders taught these poor rural workers that new politicians would get back what had been taken from them. The poor did not realize that they were being used for political purposes. In the Indian city of Izalco, the uprising was severe, and the military reaction was also severe. Though there is no official record, it is known that Leopoldo Chávez, a good evangelical Christian, who came from a well-known evangelical family led a small group of evangelicals in this uprising. He, along with José Feliciano Ama, a well-known leader in the communist party, were both hung on the plaza in front of La Asunción Catholic Church. This was probably one of the greatest symbols of the ideological contradictions that plagued the poor of that era, a radical communist and an evangelical Christian that found unity of cause and similarity in death. A Baptist missionary, Charles Detweiler related how some of the Baptist were executed by the government without proof that the Baptist had been involved in the uprising.

The new missionaries that arrived after the uprising of 1932 were, for the most part, fundamentalists. They emphasized a spiritual dimension that centered on the individual and his calling. They proposed a radical separation from the world on the part of the church. This, of course, included the avoidance of any participation by church members in any area of politics. They used Leopoldo Chávez as an example of mixing politics with religion. This internalization by the evangelical churches produced an atmosphere of individualism, fatalism, and economic self-determinism. For the most part, the churches´ attitude was that politics was a worldly system to be avoided by Christians.

During the post-World War II era, the North American missionaries, following North American social and political tenets, preached and taught the evils of communism and a separation from political involvement. The evangelical churches were taught that communism meant materialism, anti-Christ, and therefore, anti-church. During the cold war period that included the decades of the 40s, 50s, and 60s, Salvadoran Protestant leaders maintained an anti-political involvement, especially an anti-communism idea that characterized the Salvadorean churches. Reports and testimonies began to appear of the anti-God attitude of the Cuban 1958 revolution coupled with testimonies of the treatment given Christians by the Castro regime. These reports confirmed the already anti-communistic position of the local pastors.

EVANGELICALS IN THE TIME OF REVOLUTION

When violence began in El Salvador in 1979, most evangelical churches were generally opposed to the revolutionary movements. First, North American missionaries, working with various evangelical groups, promoted the Cold War ideas that the left was communistic, and therefore, anti-God. Secondly, leftist organizations were viewed as a violent form of political activism. Being that the evangelicals had had one bad experience of political involvement in the 1932 uprising, and being that most evangelicals were nonviolent in nature, the call to the revolution fell on deaf evangelical ears.

Since the beginning of the civil conflict in El Salvador, Catholic priests and Protestant pastors have been murdered. Eight Catholic priests were killed from 1977 through 1980, including Archbishop Oscar Romero and later the well-known priest, Father Rutilio Grande. From 1980 till 1989 another 12 priests were killed by government death squads. More recently, six more priests were slain in cold blood inside their living compound at the Universidad Centroamericana José‚ Simeón Cañas. These priests were assassinated due to their active support of the FMLN.

There is much evidence that concludes that these priests were executed due to their close association with the FMLN as evidenced by their writings and sermons during mass. It has been reported that as many as 50 Salvadoran evangelical pastors have also been murdered, but these by the revolutionary groups. Due to the growing evangelical population and their diverse and disaggregated organizations, there has been no means to confirm most of their deaths.

Verified data has been collected on twelve murdered pastors showing conclusively that FMLN guerrillas killed these defenseless pastors for two reasons: One reason was that the pastors opposed the civil war and the leftist political position held by the Salvadoran guerrillas. Due to the influence that these pastors maintained in their local community, the local FMLN leaders decided to murder them in order to silence these opposing voices. Another reason for the pastors’ cold-blooded murders was the simple fact that their messages were direct extensions of North American interference in Salvadoran internal affairs. For the FMLN leadership, evangelical Christian practice and current Marxist philosophy are antithetical, the comandantes of the guerrilla forces silenced the expressions of local evangelical leaders who vocally opposed the subversive war against the Salvadoran government.

Names of Evangelical Pastors Murdered by FMLN in El Salvador verified by Paralife.

Name Church City Date

Amadeo de Jesus Avalos, Profetica Batel, Soyapango Agosto 1988

Susana Veralice Miranda Lirios del Valle, Santa Ana Dic, 1988

Pacifico Alas El Nasareno, El Paisnal 1982

Carlos Diaz Iglesia de Dios, Peñanolapa Sept, 1986

Juan de Dios Quezada Iglesia “Hermosa” Chalatenango ???

Alfredo Lainez Asambleas de Dios Zacatecoluca 1983

Tomás Miranda Apostoles & Prof Guayabal Agosto 1984

José Miranda Apostoles & Prof Guayabal Agosto 1984

Evangelical Cooperation and Development

From the beginning it was very difficult for evangelicals to have any community influence in the neighborhoods where churches were located. One reason was the overwhelming Catholic influence that prevailed. Another reason was the fractured evangelical community itself. In one community there might be one Catholic church, however, one might find as many as a dozen or more different small evangelical churches. Collective attendance on any given Sunday of all the evangelical churches might surpass the attendance of the Catholic mass, but it was still the Catholic influence that was predominant in the area. Besides the many different groups in El Salvador, they were generally very competitive among themselves. Each denomination had a doctrine that was taught to its adherents. In many instances, adherence to a single doctrine was the basis of fellowship in the different localities. Therefore, not only were the evangelicals opposing the Catholic church, but also all other small evangelical churches as well. Though in the larger cities, the intensity of this interchurch competition may have been less intense, rivalry was still very strong.

This fissure in the evangelical movement limited it for another reason. Whereas the archbishop of San Salvador can speak for the Catholic church, there was no one person that could speak for the varied and many evangelical churches. This made it most difficult for the evangelicals when they needed to take a collective position on any issue. Because of the above-mentioned problems, only a hand full of evangelicals prevented disaster for the movement. During the previous 50 years the Catholic church had petitioned the legislative assembly on three different occasions for rights to be the official church of El Salvador. Had it not been for a few strong men in the assembly who advised various evangelical leaders of the impending legislation, a great threat to the existence of the evangelical bodies could have been made law. Instead, the evangelical leaders made strong appeals to various legislature members who were able to defeat the proposal. The point is, there was not even a consensus on the part of the evangelicals for the action of the few church leaders who, with God’s help, stayed legislative action that would have certainly hindered the work of the Lord in El Salvador. “It is encouraging to note that since the mid-1980s, we have seen more cooperation of evangelical leaders in the metropolitan areas” remarked one influential pastor. This cooperation has been seen in the organization of special prayer events and other interchurch functions.

One of the greatest events that generated interchurch activity was evangelistic campaigns. Recently, various evangelists have come to El Salvador with large and impressive campaigns. The secret that has made these campaigns successful has been the cooperation of as many as 100 different churches from 20 different organizations.

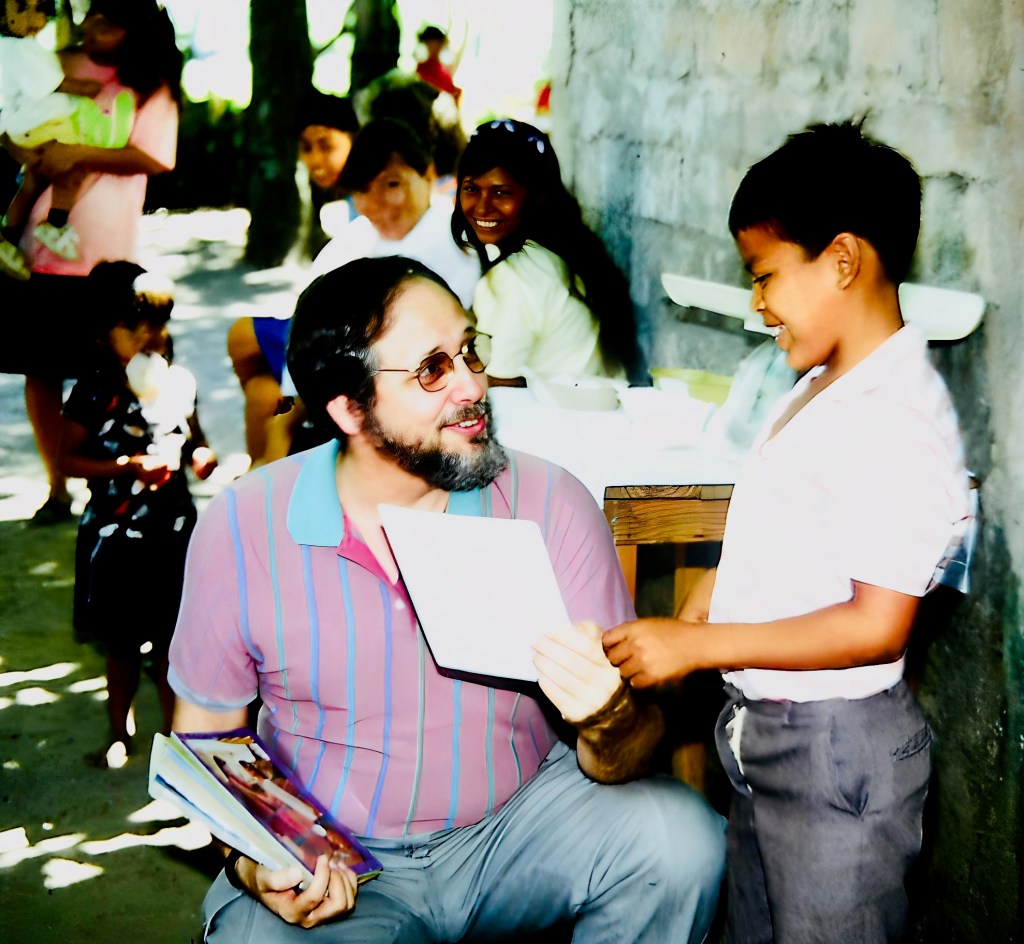

Another indication that more cooperation had developed among evangelical churches was the participation of many different churches in the programs of Paralife International in El Salvador. Not only was the staff comprised of people from different church backgrounds, but also, the projects that were undertaken included a variety of churches throughout the country. The result of interchurch activity was remarkable. “We are now receiving requests from various churches asking for help” noted the president of Paralife recently. Often that help came from another church which was gratefully received by the petitioning body.

The Current evangelical Situation

The President of Paralife International recently estimated that only three percent of the non-Catholic churches are politically active. Only three church groups have been involved in action that could be described as political in nature. Those three groups are the Episcopal church, the Lutheran church, and Emanual Baptist church. “By and large,” he continued, “the Salvadoran evangelicals feel that politics is a dirty business, and they want no part of it. Almost 100 % of the other church groups will support the present government or the government that is democratically elected. These churches generally feel that Paul and Peter were speaking to them regarding the honor and respect due their civil leaders.”

In fact, this may be one reasons why evangelical churches have grown so rapidly during the recent years. Whereas the Catholic church took a very sharp turn from its traditional teachings and strongly attempted to influence political issues that were pro-FMLN. As a consequence, many Catholics laity sought out and turned to the evangelical church as a refuge. Many people who were previously Catholic, felt that they were not abandoning their church, but rather, that their church had abandoned them. The middle class was tired of political treatises that blamed them for the conditions of the poor and at the same time encouraged the poor to steal from their employers. In most evangelical churches, the message remained strictly doctrinal, extending both a spiritual and terrestrial hope for tomorrow. Though often the church buildings were humble adobe structures, they heard sermons dealing with honesty, morality, and the power of the Holy Spirit in one’s life. The messages were generally centered on Christ and themes that dealt with His kingdom.

Salvadoran evangelical churches grew rapidly during the days of political unrest. Not only did these churches reach the very poor, but also they reached the professional middle class. Since their arrival in El Salvador, the evangelicals generally found their converts among the very poor. However, since 1979 an even greater number of poor have joined Protestant churches along with middle class professionals. It is interesting that these are the very people for whom the Catholic church had so strongly stated its preferential option.

There are several reasons why the evangelical churches have grown so rapidly. First, it seems that people tend to look to God during crisis. Since evangelicals offer a religious experience that is more intense and participatory, it is not surprising that people would look to them during crisis. Another reason is that there were many more evangelical leaders and pastors. It generally takes seven years for the Catholic church to produce a priest, whereas, evangelicals could have a pastor trained and preaching in a pulpit within months. And another reason that evangelicals have grown so rapidly is that they are perceived as being anti-communist. With the Catholic church’s apparent tilt to the left, the evangelicals offer a more familiar message.

The evangelicals not only have grown in number, but they have also grown in prestige and social maturity as many middle class citizens opted for evangelical membership. Today, many of the urban evangelical churches are large and well-designed edifices. Many of these churches also sponsor Christian schools. The Assembly of God school program is the largest with approximately 20 schools and 16,000 students. Many of the evangelical schools have clinics that attend students and their families´ medical needs . Although most evangelical schools are in the capital city, Paralife International and Compassion International operate schools in the rural areas.

Salvadorean Churches and Membership

Denominations Members Churches

Assemblies of God 400 900

Apostles and Prophets 150 200

Independent Pentecostals 80 220

Central American Mission 65 100

Church of God 60 215

Prince of Peace 60 180

United Pentecostal 60 100

Independent Baptist 55 100

Elim 40 50

Holy Zion 40 80

American Baptist 25 70

Free Apostles 17 70

Universal Prophecy 14 54

Four Square Church 14 50

Latin American Council 3 42

Nazarene 10 16

Lutheran 4 26

Independent Churches 50 200

Other 250 300

Total 1,407,000 2,87

Conclusion

A major shift in religious affiliation has taken place in El Salvador since 1979. This does not mean that the evangelicals have taken the number 1 status, but it does indicate that evangelicals will be a power to deal with in the future. As they become more organized and more educated, they will play a part in future political contest. The evangelical church will likely expand its political power on issues with a moral dimension and remain strongly anti-left. But given their bias against political activism and their internal fracturalization, any union for a political cause seems most unlikely. This is not to say that they would not rally around a single evangelical personality who stepped into the political arena.

One more consideration must be taken. The youth of the present evangelicals do not remember the political and economic risks that were involved in the 1932 uprising. Neither were they around during the Cold War period and, consequently, they have not been exposed to the negative side of communism. Under the present cloud of violence and political unrest, North American missionaries and local pastors have not been as energetic to preach anti-communistic messages. Therefore, the youth of El Salvador are in danger of accepting the humanistic-marxistic teachings of the left. The introduction of Liberation Theology to El Salvador and its “Christian Marxism” declarations, have had a definite magnetic effect on many of the younger evangelical members from the lower socioeconomic levels.

Reviewed October 1992